Making Decisions in an Uncertain World

The stock market is inherently unpredictable. Even with detailed research and analysis, uncertainty cannot be eliminated. Yet, many investors still judge the quality of their decisions purely by the eventual outcome, even though that outcome could not have been known at the point of decision.

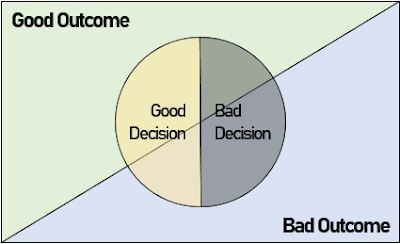

Good Decisions Can Look Bad, and Bad Decisions can Look Good

A poor decision (e.g., making an oversized bet on a highly speculative stock) can sometimes result in a strong payoff purely by luck. When this happens, the investor may mistakenly attribute the positive outcome to skill, reinforcing behaviour that is ultimately fragile and unsustainable.

Conversely, a sound decision can produce disappointing results. Allocating capital to a broad, low-cost global equity index is supported by decades of evidence and is a rational strategy for long-term wealth accumulation. But in the short to medium term, markets can underperform expectations. If an investor judges their decision solely by these short-term results, they may abandon a sensible strategy prematurely.

We can illustrate this using a simple investment outcome uncertainty matrix

Even a well-reasoned decision can produce a poor outcome, and a poorly reasoned decision can occasionally turn out well by chance. Because outcomes are influenced by randomness, they do not reliably indicate the quality of the decision itself. Evaluating investments based solely on results therefore leads to misleading conclusions.

Focus on the Decision Process, Not the Outcome

A more robust approach is to evaluate the reasoning behind the investment decision itself:

- Was the decision supported by evidence?

- Was the risk understood?

- Was the position size appropriate?

- Was the strategy diversified enough to withstand uncertainty?

For example, investing in a diversified broad market index is generally justified by the existence of the market risk premium, a well-established phenomenon that stocks, over long horizons, tend to outperform risk-free assets as compensation for risk. This is rooted in basic risk-aversion behaviour: investors demand compensation for bearing uncertainty, which collectively pushes expected returns higher.

In contrast, concentrating heavily in a single stock exposes the investor to idiosyncratic risk, which is not compensated. Empirical studies consistently show that very few stock pickers outperform the market over time. Outperformance may occur occasionally, but persistence is rare.

Diversification as Risk ManagementEven good decisions carry uncertainty. For example, investing solely in the U.S. equity market in 2001 would have underperformed the risk-free 10-year Treasury by roughly 3.18% per year over the subsequent decade. The strategy was sensible; the outcome was not.

However, a diversified allocation, such as spreading investments across U.S., developed ex-U.S., and emerging markets, would have produced a positive excess return of around 1.78% per year over the same period. Diversification does not eliminate risk, but it reduces exposure to being wrong in one place at one time.

Discipline Matters More Than Predictions

A sound strategy is only effective if you stick with it. Periods of high volatility trigger fear and overreaction. An investor who capitulated and sold equities during the depths of the 2008–2009 financial crisis would have missed the substantial recovery and expansion over the next decade.

The goal is not to avoid loss entirely, but to ensure that your decisions are:

- Rational rather than emotional

- Supported by evidence rather than narratives

- Diversified rather than concentrated

- Consistent rather than reactive

In short, judge your decisions by their reasoning, not by the randomness of outcomes. Good processes compound. Outcomes eventually follow.

The views in this post reflect my own opinions and are not financial advice. You should not treat anything shared by someone online, including this, as a basis for making financial decisions, regardless of how confident or persuasive it sounds.

Comments

Post a Comment